“Am I doing it right?” asked the Sea Lady.

Formats Used: Audiobook + Online Text

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/35920/35920-h/35920-h.htm

Summary

A mermaid called the Sea Lady visits an English family known as The Buntings; ostensibly to learn about the modern world. But her real goal is to initiate an affair with the handsome, charming, moderately wealthy young gentleman named Harry Chatteris. He is running for political office and has an extremely beautiful fiance: the religious and social propagandist Adeline Glendower. But his life is sterile consisting only of work and duty. The Sea Lady offers a departure into the Great Outside, “There are better dreams…” she says.

As soon as they had reached the high-watermark where it is no longer indecent to be clad merely in a bathing dress; each of the young ladies handed her attendant her wrap, and after a little fun and laughter Mrs. Bunting looked carefully to see if there were any jellyfish, and then they went in. And after a minute or so, it seems Betty, the elder Miss Bunting, stopped splashing and looked, and then they all looked, and there, about thirty yards away was the Sea Lady’s head, as if she were swimming back to land.

Naturally they concluded that she must be a neighbour from one of the adjacent houses. They were a little surprised not to have noticed her going down into the water, but beyond that her apparition had no shadow of wonder for them. They made the furtive penetrating observations usual in such cases. They could see that she was swimming very gracefully and that she had a lovely face and very beautiful arms, but they could not see her wonderful golden hair because all that was hidden in a fashionable Phrygian bathing cap, picked up—as she afterward admitted to my second cousin—some nights before upon a Norman Plage. Nor could they see her lovely shoulders because of the red costume she wore.

And it is a curious thing that the Sea Lady was at least a minute out of the water before anyone discovered that she was in any way different from—other ladies. I suppose they were all crowding close to her and looking at her beautiful face, or perhaps they imagined that she was wearing some indiscreet but novel form of dark riding habit or something of that sort. Anyhow not one of them noticed it, although it must have been before their eyes as plain as day. Certainly it must have blended with the costume. And there they stood, imagining that Fred had rescued a lovely lady of indisputable fashion, who had been bathing from some neighboring house, and wondering why on earth there was nobody on the beach to claim her. And she clung to Fred and, as Miss Mabel Glendower subsequently remarked in the course of conversation with him, Fred clung to her.

Indeed it was conspicuous. It was some way below high water and the group stood out perhaps thirty yards down the beach. Nobody, as Mrs. Bunting told my cousin Melville, knew a bit what to do and they all had even an exaggerated share of the national hatred of being seen in a puzzle. The mermaid seemed content to remain a beautiful problem clinging to Fred, and by all accounts she was a reasonable burthen for a man. It seems that the very large family of people who were stopping at the house called Koot Hoomi had appeared in force, and they were all staring and gesticulating. They were just the sort of people the Buntings did not want to know—tradespeople very probably. Presently one of the men—the particularly vulgar man who used to shoot at the gulls—began putting down their ladder as if he intended to offer advice, and Mrs. Bunting also became aware of the black glare of the field glasses of a still more horrid man to the west.

One can figure the little procession. In front Fred, wet and astonished but still clinging and clung to, and altogether too out of breath for words. And in his arms the Sea Lady. She had a beautiful figure, I understand, until that horrible tail began (and the fin of it, Mrs. Bunting told my cousin in a whispered confidence, went up and down and with pointed corners for all the world like a mackerel’s). It flopped and dripped along the path—I imagine. She was wearing a very nice and very long-skirted dress of red material trimmed with course white lace, and she had, Mabel told me, a giley, though that would scarcely show as they went up the garden. And that Phrygian cap hid all her golden hair and showed the white, low, level forehead over her sea-blue eyes. From that followed, I imagine her at the moment scanning the veranda and windows with a certain eagerness of scrutiny.

Her treatment of Mrs. Bunting would be incredible if we did not know that, in spite of many disadvantages, the Sea Lady was an extremely well read person. She admitted as much in several later conversations with my cousin Melville. For a time there was a friendly intimacy—so Melville always preferred to present it—between these two, and my cousin who has a fairly considerable amount of curiosity, learnt many very interesting details about the life “out there” or “down there”—for the Sea Lady used either expression. At first the Sea Lady was exceedingly reticent under the gentle insistence of his curiosity, but after a time, I gather, she gave way to bursts of cheerful confidence. “It is clear,” says my cousin, “that the old ideas of the submarine life as a sort of perpetual game of ‘who-hoop’ through groves of coral, diversified by moonlit hair-combings on rocky strands, need very extensive modification.” In this matter of literature for example, they have practically all that we have, and unlimited leisure to read it in! Melville is very insistent upon and rather envious of that unlimited leisure. A picture of a mermaid swinging in a hammock of woven seaweed, with what biships call a “latter-day” novel in one hand and a sixteen candle-power phosphorescent fish in the other, may jar upon one’s preconceptions, but it is certainly far more in accordance with the picture of the abyss she printed on his mind. Everywhere change works her will on things. Everywhere, and even among the immortals, Modernity spreads. Even on Olympus I suppose there is a Progressive party and a new Phaeton agitating to supersede the horses of his father, by some solar motor of his own. I suggested as much to Melville and he said “Horrible! Horrible!” and stared hard at my study fire. Dear old Melville! She gave him no end of facts about Deep Sea Reading.

This modern world is a world where the wonderful is utterly commonplace. We are bred to show a quiet freedom from amazement, and why should we boggle at material Mermaids, with Dewars solidifying all sorts of impalpable things and Marconi waves spreading everywhere? To the Buntings she was as matter of fact, as much a matter of authentic and reasonable motives and of sound solid sentimentality, as everything else in the Bunting world. So she was for them in the beginning and so up to this day with them her memory remains.

“Exactly—yes. And it really seems these poor creatures are Immortal Mr. Melville—at least within limits—creatures born of the elements and resolved into the elements again—and just as it is in the story—there’s always a something—they have no Souls! No Soul at all! Nothing! And the poor child feels it. She feels it dreadfully. But in order to get souls, Mr. Melville, you know they have to come into the world of men. At least, so they believe down there. And so she has come to Falkestone. To get a soul. Of course that’s her great object, Mr. Melville, but she’s not at all fanatical or silly about it. Anymore than we are of course. We—people who feel deeply—“

“Of course,” said my cousin Melville, with, I know, a momentary expression of profound gravity, drooping eyelids and a hushed voice. For my cousin does a good deal with his soul, one way or another.

“And she feels that if she comes to earth at all,” said Mrs. Bunting, “She must come among nice people in a nice way. One can understand her feeling like that. But imagine her difficulties! To be a mere cause of public excitement, and silly paragraphs in the silly season, to be made to be a sort of show of, in fact—she she doesn’t want any of it,” added Mrs. Bunting, with the emphasis of both hauds.

“What does she want?” asked my cousin Melville.

She wants to be treated exactly like a human being, to be a human being, just like you or me. And she asks to stay with us, to be one of our family, and to learn how we live. She has asked me to advice her what books to read that are really nice, and where she can get a dress-maker, and how she can find a clergyman to sit under who would really be likely to understand her case, and everything. She wants me to advise her about it all. She wants to put herself altogether in my hands. And she asked it all so nicely and sweetly. She wants me to advise her about it all.”

I gather that the three ladies sat and talked as any three ladies all quite resolved to be pleasant to one another would talk. Mrs. Bunting and Miss Glendower were far too well trained in the observances of good society (which is as everyone knows, even the best of it now, extremely mixed) to make too searching enquiries into the Sea Lady’s status and way of life or precisely where she lived when she was at home, or whom she knew or didn’t know. Though in their several ways they wanted to know badly enough. The Sea Lady volunteered no information, contenting herself with an entertaining superficiality of touch and go, in the most ladylike way. She professed herself greatly delighted with the sensation of being in air and superficially quite dry, and was particularly charmed with tea.

Mrs. Bunting made a little coo of approval. She was reminded of chrysanthemum shows and the outside of the Royal Academy exhibition and she was one of those people to whom only the familiar is really satisfying. She had a momentary vision of the abyss as a sort of diverticulum of Piccadilly and the Temple, a place unexpectedly rational and comfortable. There was a kink for a time about a little matter of illumination, but it recurred to Mrs. Bunting only long after. The Sea Lady had turned from Miss Glendower’s interrogative gravity of expression to the sunlight.

She regarded them for a moment with a frank wonder, the undying wonder of the Immortals at that perpetual decay and death and replacement which is the gist of human life. Then at the expression of their faces she seemed to recollect. “Of course,” she said, and then with a transition that made pursuit difficult, she agreed with Adeline. “It is different,” she said. “It is wonderful. One feels so alike, you know, and so different. That’s just where it is so wonderful. Do I look—? And yet you know I have never had my ahir up, nor worn a dressing gown before today.”

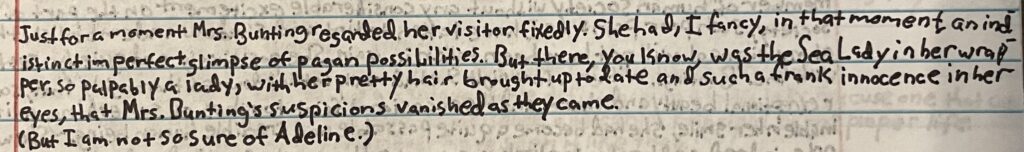

Just for a moment Mrs. Bunting regarded her visitor fixedly. She had, I fancy, in that moment, an indistinct imperfect glimpse of pagan possibilities. But there, you know, was the Sea Lady in her wrapper, so palpably a lady, with her pretty hair brought up to date and such a frank innocence in here eyes, that Mrs. Bunting’s suspicions vanished as they came.

(But I am not so sure of Adeline.)

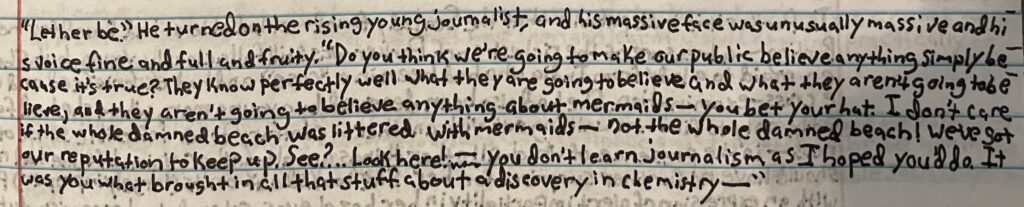

“Let her be.” He turned on the rising young journalist, and his massive face was unusually massive and his voice fine and full and fruity. “Do you think we’re going to make our public believe anything simply because it’s true? They know perfectly well what they are going to believe and what they aren’t going to believe, and they aren’t going to believe anything about mermaids—you bet your hat. I don’t care if the whole damned beach was littered with mermaids—not the whole damned beach! We’ve got our reputation to keep up. See?… Look here!—you don’t learn journalism as I hoped you’d do. It was you what brought in all that stuff about a discovery in chemistry—”

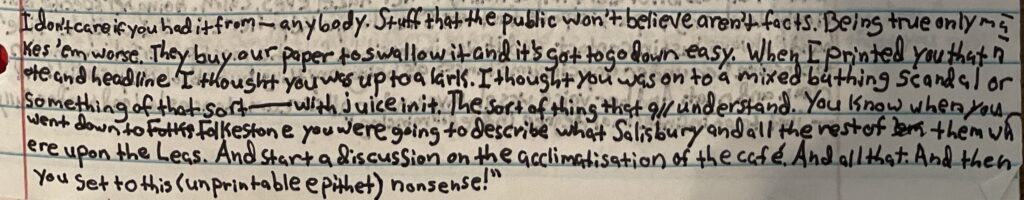

“I don’t care if you had it from—anybody. Stuff that the public won’t believe aren’t facts. Being true only makes ’em worse. They buy our paper to swallow it and it’s got to go down easy. When I printed you that note and headline I thought you was up to a lark. I thought you was on to a mixed bathing scandal or something of that sort—with juice in it. The sort of thing that all understand. You know when you went down to Folkestone you were going to describe what Salisbury and all the rest of them where upon the Leas. And start a discussion on the acclimatisation of the cafe. And all that. And then you get to this (unprintable epithet) nonsense!”

“Stuff that the public won’t believe aren’t facts.”

It must have been quite soon after that, that I myself heard the first mention of the mermaid, little recking that at last it would fall on me to write her history. I was on one of my rare visits to London, and Micklethwaite was giving me lunch at the Penwiper Club, certainly one of the best dozen literary clubs in London. I noticed the rising young journalist at a table near the door, lunching alone. All about him tables were vacant, though the other parts of the room were crowded. He sat with his face towards the door, and he kept looking up whenever any one came in, as if he expected someone who never came. Once distinctly I saw him beckon to a man, but the man did not respond.

I turned my mind to feigning an interest in golf— a game that in truth I despise and hate as I despise and hate nothing else in this world. Imagine a great fat creature like Micklethwaite, a creature who ought to wear a turban and a long black robe to hide his grossness, whacking a little white ball for miles and miles with a perfect surgery of instruments, whacking it either with a babyish solemnity or a childish rage as luck may have decided, whacking away while his country goes to the devil, and incidentally training an innocent eyed little boy to sweat and be a tip-hunting loafer. That’s golf! However, I controlled my all too facile sneer and talked of golf and the relative merits of golf links as I might talk to a child about buns or distract a puppy with the whisper of “rats,” and when at last I could look at the rising young journalist again our lunch had come to an end.

So far I have been very full, I know, and verisimilitude has been my watchword rather than the true affidavit style. But if I have made it clear to the reader just how the Sea Lady landed and just how possible it was for her to land and become a member of human society without any considerable excitement on the part of that society, such poor pains as I have taken to tint and shadow and embellish the facts at my disposal will not have been taken in vain. She positively and quietly settled down with the Buntings. Within a fortnight she had really settled down so thoroughly that, save for her exceptional beauty and charm and the occasional faint touches of something a little indefinable in her smile, she had become a quite passable and credible human being. She was a cripple, indeed, and her lower limb was most pathetically swathed and put in a sort of case, but it was quite generally understood—I am afraid at Mrs. Bunting’s initiative—that presently they—Mrs. Bunting said “they,” which was certainly almost as far or even a little farther than the legitimate prevarication may go—would be as well as ever.

She positively and quietly settled down with the Buntings.

In Parker it is indisputable that the Sea Lady found—or had at least had found for her by Mrs. Bunting—a treasure of the richest sort. Parker was still fallaciously young, but she had been maid to a lady from India who had been in a “case” and had experienced and overcome cross-examination. She had also been deceived by a young man, whom she had fancied greatly, only to find him walking out with another—contrary to her inflexible sense of correctness—in the presence of which all other things are altogether vain. Life she had resolved should have no further surprises for her. She looked out on its (largely improper) pageant with an expression of alert impartiality in her hazel eyes, calm, doing her specific duty, and entirely declining to participate further. She always kept her elbows down by her side and her hands always just in contact, and it was impossible for the most powerful imagination to conceive her under any circumstances as being anything but absolutely straight and clean and neat. And her voice was always under all circumstances low and wonderfully distinct—just to an infintesimal degree indeed “mincing.”

She was not only discreet but really clever and handy. From the very outset she grasped the situation, unostentatiously but very firmly. It was Parker who contrived the sort of violin case for It, and who made the tea gown extension that covered the case’s arid contours. It was Parker who suggested an invalid’s chair for use indoors and in the garden, and a carrying chair for the staircase. Hitherto Fred Bunting had been on hand, at last even in excessive abundance, whenever the Sea Lady lay in need of masculine arms. But Parker made it clear at once that that was not in accordance with her ideas, and so earned the lifelong gratitude of Mabel Glendower. And Parker too spoke out for drives, and suggested with an air of rightness that left nothing else to be done, the hire of a carriage and pair for the season—to the equal delight of the Buntings and the Sea Lady. It was Parker who dictated the daily drive up the eastern end of the Leas and the Sea Lady’s transfer, and the manner of the Sea Lady’s transfer, to the bathchair in which she promenaded the Leas. There seemed to be nowhere that it was pleasant and proper for the Sea Lady to go that Parker did not swiftly and correctly indicate it and the way to get to it; and there seems to have been nothing that it was really undesirable the Sea Lady should do and anywhere that it was really undesirable that she should go, that Parker did not at once invisibly but effectively impose a bar. It was Parker who released the Sea Lady from being a sort of private and peculiar property in the Bunting household and carried her off to a becoming position in the world when the crisis came. In little things as in great she failed not. It was she who made it luminous that the Sea Lady’s card plate was not yet engraved and printed (“Miss Doris Thalassia Waters” was the pleasant and appropriate name which the Sea Lady came primed), and who replaced the box of the presumably dank and drowned and dripping “Tom” by jewel case, a dressing bag and the first of the Sea Lady’s trunks.

On a thousand little occasions this Parker showed a sense of propriety that was penetratingly fine. For example, in the shop one day when “things” of an intimate sort were being purchased, she suddenly intervened.

“There are stockings, Mem,” she said in a discreet undertone, behind, but not too vulgarly behind, a fluttering straight hand.

“Stockings!” cried Mrs. Bunting. “But—!”

“I think, Mem, she should have stockings,” said Parker, quietly but very firmly.

And come to think of it, why should an unavoidable deficiency in a lady excuse one that can be avoided. It’s there we touch the very quintessence and central principle of the proper life. But Mrs. Bunting, you know, would never have seen it like that.

I must confess, with a slight tinge of humiliation, that I pursued this young woman [Parker] to her present situation at Hightori Towers—maid she is to that eminent religious and social propogandist, the Lady Jane Glanville. There were certain details of which I stood in need, certain scenes and conversations for which my passion for verisimiltude had scarcely a crumb to go upon. And from first to last, what she must have seen and learnt would amount practically to everything.

And, in spite of what became at last very fine and handsome inducements, that remained the inflexible Parker’s reply. Even after I had come to an end with my finesse and attempted to bribe her in the grossest manner, she displayed nothing but a becoming respect for my inpregnable social superiority.

“I couldn’t think of it, sir,” she repeated. “It wouldn’t be at all according to my ideas.” And if in the end you should find this story to any extent vague or incomplete, I trust you will remember how the inflexible severity of Parker’s ideas stood in my way.

“Oh, she doesn’t contradict. But she—There is something about her—One feels that things that are most important and vital are nothing to her. Don’t you feel it? She comes from another world to us.”

“I’m sure in these days, with so much materialism about and such wickedness everywhere, when everybody who has a soul seems trying to lose it, to find anyone who hadn’t a soul and who is trying to find one—“

But is she trying to get one?”

“Mr. Flange comes twice every week. He could come oftener, as you know, if there wasn’t so much confirmation about.”

And when he comes he sits and touches her hand if he can, and he talks in his lowest voice, and she sits and smiles—she almost laughs outright at the things he says.”

“Because he has to win his way with her. Surely Mr. Flange may do what he can to make religion attractive?”

“I don’t believe she believes she will get a soul. I don’t believe she wants one a bit.”

Within an hour they all met at the luncheon table and Adeline’s behavior to the Sea Lady and to Mrs. Bunting was as pleasant and alert as any highly earnest and intellectual young lady’s could be. And all that Mrs. Bunting said and did tended with what people call infinite tact—which really, you know, means a great deal more tact than is comfortable—to develop and expose the more serious aspect of the Sea Lady’s mind. Mr. Bunting was unusually talkative and told them all about a glorious project he had heard of to cut out the rather shrubby and weedy front of the Leas and stick in something between a wine vault and the Crystal Palace as a Winter Garden—which seemed to him a very excellent idea indeed.

The last Melville regarded as the most heinous offence. It is not the least of my cousin’s weaknesses that he regards this great novelist as an extremely corrupting influence for intelligent girls. She makes them good and serious in the wrong way, he says. Adeline, he asserts, was absolutely built on her. She was always attempting to be the incarnation of Marcella. It was he who had perverted Mrs. Bunting’s mind to adopt this fancy. But I don’t believe for a moment in this idea of girls building themselves on heroines in fiction. These are matters of elective affinity, and unless some bullying critic or preacher sends us astray, we take each to our own novelist as the souls in the Swedenborgian system take to their hells. Adeline took to the imaginary Marcella. There was, Melville says, the strongest likeness in their mental atmosphere. They had the same defects, a bias for superiority—to use his expressive phrase—the same disposition towards arrogant benevolence, that same obtuseness to little shades of feeling that lead people to speak habitually of the “Lower Classes,” and to think in the vein of that phrase. They certainly had the same virtues, a conscious and conscientious integrity, a hard nobility without one touch of magic, an industrious thoroughness. More than in anything else, Adeline delighted in her novelist’s thoroughness, her freedom from impressionism, the patient resolution with which she went into the corners and swept under the mat of every incident. And it would be easy to argue form that, that Adeline behaved as Mrs. Ward’s most characteristic heroine behaved, on analogous occasion.

Marcella we know—at least after her heart was changed—would have clung to him. There would have been a moment of high emotion in which thoughts—of the highest class—mingled with the natural ambition of two people in the prime of life and power. Then she would have receded with a quick movement and listened with her beautiful hand pensive against her cheek, while Chatteris began to sum up the forces against him—to speculate on the action of this group and that. Something infinitely tender and maternal would have spoken in her, pledging her to the utmost help that love and a woman can give. She would have produced in Chatteris that exquisite mingled impression of grace, passion, self yielding, which in all its infinite variations and repetitions made up for him the constant poem of her beauty.

But that is the dream and not the reality. So Adeline might have dreamt of behaving, but she was not Marcella, and only wanting to be, and he was not only not Maxwell but he had no intention of being Maxwell anyhow. If he had had an opportunity of becoming Maxwell he would probablly have rejected it with extreme incivility. So they met like two unheroic human beings with shy and clumsy movements and, I suppose, fairly honest eyes. Something there was in the nature of a caress, I believe, and then I incline to fancy she said “Well?” and I think he must have answered, “It’s all right.” After that, and rather allusively, with a backward jerk of the head at intervals as it were towards the great personage, Chatteris must have told her particulars. He must have told her that he was going to contest Hythe and that the little difficulty with the Glasgow commission agent who wanted to run the Radical ticket as a “Man of Kent” had been settled without injury to the party (such as it is). Assuredly they talked politics, because soon after, when they came into the garden side by side to where Mrs. Bunting and the Sea Lady sat watching the girls play croquet, Adeline was in full possession of all these facts. I fancy that for such a couple as they were, such intimation of success, such earnest topics, replaced, to a certain extent at any rate, the vain repetition of vulgar endearments.

No one seemed to take the slightest notice of Adeline’s dramatic announcement. The Buntings were not good at thinking of things to say. She stood in the midst of the group like a leading lady when the other actors have forgotten their parts. Then every one woke up to this, as it were, and they went off in a volley. “So it’s really all settled,” said Mrs. Bunting; and Betty Bunting said, “There is to be an election then!” and Nettle said, “What fun!” Mr. Bunting remarked with a knowing air, “So you saw him then?” and Fred flung “Hooray!” into the tangle of sounds.

The Sea Lady of course said nothing.

Then came a pause, and Mr. Bunting was emboldened to lift up his voice and utter politics. “They are getting sense,” he said. “They are learning that a party must have men, men of birth and training. Money and the mob—they’ve tried to keep things going by playing to fads and class jealousies. And the Irish. And they’ve had their lesson. How? Why,—we’ve stood aside. We’ve left ’em to faddists and fomentors—and the Irish. And here they are! It’s a revolution in the party. We’ve let it down. Now we must pick it up again.”

A little group about the Sea Lady’s bath chair.

“She’s interesting. Her illness seems to throw her up. It makes a passive thing of her, like a picture or something that’s imaginary. Imagined—anyhow. She sits there and smiles and responds. Her eyes—have something intimate. And yet—“

My cousin offered no assistance.

“Where did Mrs. Bunting find her.”

My cousin had to gather himself together for a second or so.

“There’s something,” he said deliberately, “that Mrs. Bunting doesn’t seem disposed—“

“What can it be?”

It’s bound to be all right,” said Melville rather weakly.

It’s strange, too. Mrs. Bunting is usually so disposed—“

Melville left that to itself.

“That’s what one feels,” said Chatteris.

“What?”

“Mystery.”

My cousin shares with me a profound detestation of that high mystic method of treating women. He likes women to be finite—and nice. In fact, he likes everything to be finite—and nice. So he merely grunted.

But Chatteris was not to be stopped by that. He passed to a critical note. “No doubt it’s all illusion. All women are impressionists, a patch, a light. You get an effect. And that is all you are meant to get, I suppose. She gets an effect. But how—that’s the mystery. It’s not merely beauty. There’s plenty of beauty in the world. But not of these effects. The eyes, I fancy.”

He dwelt on that for a moment.

There’s really nothing in eyes, you know, Chatteris,” said my cousin Mellville, borrowing an alien argument and a tone of analytical cynicism from me.

Have you ever looked at eyes through a hole in a sheet?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Chatteris. “I don’t mean the mere physical eye… perhaps it’s the look of health—and the bath chair. A bold discord. You don’t know what’s the matter, Melville?”

“How?”

I gather from Bunting it’s a disablement—not a deformity.”

These two, I say, were sitting in the ample shade under the evergreen oak, and Melville, I imagine was in those fine faintly patterned flannels that in the year 1899 combined correctness with ease. He was no doubt looking at the shaded face of the Sea Lady, framed in a frame of sunlit yellow-green lawn and black-green ilex leaves—at least so my impulse for verisimiltude conceives it—and she at first was pensive and downcast that afternoon and afterwards she was interested and looked into his eyes. Either she must have suggested that he might smoke or else he asked. Anyhow, his cigarettes were produced. She looked at them with an arrested gesture, and he hung for a moment, doubtful on her gesture.

She accepted a cigarette and examined it thoughtfully. “Down there,” she said, “it’s just one of those things—You will understand we get nothing but saturated tobacco. Some of the mermen—There’s something they have picked up from the sailors. Quids, I think they call it. But that’s too horrid for words!”

“Am I doing it right?” asked the Sea Lady.

“Because you are immortal—and unimcumbered. Because you can do everything you want to do—and we cannot. I don’t know why we cannot, but we cannot. Here we are, with our short lives and our little souls to save, or lose, fussing for our little concerns. And you, out of the elements, come and beckon—“

“The elements have their rights,” she said. And then: “The elements are the elements, you know. That is what you forget.”

“Imagination?”

Certainly. That’s the element. Those elements of your chemists—”

“Yes?”

“Are all imagination. There isn’t any other.” She went on: “And all the elements of your life, the life you imagine you are living, the little things you must do, the little cares, the extraordinary little duties, the day by day, the hypnotic limitations—all these things are a fancy that has taken hold of you too strongly for you to shake off. You daren’t, you musn’t, you can’t. To us who watch you—“

“You watch us?”

“Oh, yes. We watch you, and sometimes we envy you. Not only for the dry air and the sunlight and the shadows of the trees, and the feeling of morning, and the pleasantness of many such things, but because your lives begin and end—because you look towards an end.”

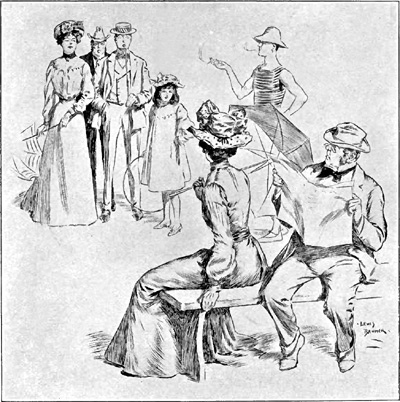

She reverted to her former topic. “But you are so limited, so tied! The little time you have, you use so poorly. You begin and you end, and all the time between it is as if you were enchanted; You are afraid to do this that would be delightful to do, you must do that, though you know all the time it is stupid and disagreeable. Just think of the things—even the little things—you musn’t do. Up there on the Leas in this hot weather all the people are sitting in stuffy ugly clothes—ever so much too much clothes, hot tight boots, you know, when they have the most lovely pink feet, some of them—we see,—and they are all the little to talk about and nothing to look at, and bound not to do all sorts of natural things and bound to do all sorts of preposterous things. Why are they bound? Why are they letting life slip by them? Just as if they wouldn’t all of them presently be dead! Suppose you were to go up there in a bathing dress and a white cotton hat—”

It wouldn’t be proper!” cried Melville.

“Why not?”

“It would be outrageous!”

“But any one might see you like that on the beach!”

“That’s different.”

“It isn’t different. You dream it’s different. And in just the same way you dream all the other things are proper or improper or good or bad to do. Because you are in a dream, a fantastic, unwholesome little dream. So small, so infintely small! I saw you the other day dreadfully worried by a spot of ink on your sleeve—almost the whole afternoon.

“Why not?”

She came warmly close to him. She spoke in gently confidential undertone, as one who imparts a secret that is not to be too lightly given. “Because,” she said, “there are better dreams.”

“Trying to be! He has to be what he is. Nothing can make him hers. If you weren’t dreaming you would see that.” My cousin was silent. “She’s not real,” she went on. “She’s a mass of fancies and vanities. She gets everything out of books. She gets herself out of a book. You can see her doing it here… What is she seeking? What is she trying to do? All this work, all this political stuff of hers? She talks of the condition of the poor! What is the condition of the poor? A dreary tossing on the bed of existence, a perpetual fear of consequences that perpetually distresses them. Lives of anxiety they lead, because they do not know what a dream the whole thing is. Suppose they were not anxious and afraid… And what does she care for the condition of the poor, after all? It is only a point of departure in her dream. In her heart she does not want their dreams to be happier, in her heart she has no passion for them, only her dream is that she should be prominently doing good, asserting herself, controlling their affairs amidst thanks and praise and blessings. Her dream! of serious things!—a rout of phantoms pursuing a phantom ignis fatuus—the afterglow of a mirage. Vanity of vanities—”

“For some there is an escape. When the whole life rushes to a moment—” And then she stopped. Now there is clearly no sense in this sentence to my mind, even from a lady of an essentially imaginary sort, who comes out of the sea. How can life rush to a moment? But whatever it was she really did say, there is no doubt she left it half unsaid.

The waiter retires amazed.

They seemed never to do anything but blow and sigh and rustle papers.

“I keep on, stepping back and looking at it,” said Chatteris. “Just lately I’ve scarcely done anything else. I’ll admit it’s a spacious and noble thing—political work done well—only—I admire it, but it doesn’t grip my imagination. That’s where the trouble comes in.”

“What does grip your imagination?” asked Melville. He was absolutely certain the Sea Lady had been talking this paralysis into Chatteris, and he wanted to see just how far she had gone. “For example,” he tested, “are there—by any chance—other dreams?”

Chatteris gave no sign at the phrase. Melville dismissed his suspicion. “What do you mean—other dreams?” asked Chatteris.

“Is there conceivably another way—another sort of life—some other aspect—?”

“It’s out of the question,” said Chatteris. He added rather remarkedly, “Adeline’s awfully good.” My cousin Melville acquiesed silently in Adeline’s goodness.

“All this, you know, is a mood. My life is made for me—and it’s a very good life. It’s better than I deserve.”

“Heaps,” said Melville.

“Much,” said Chatteris defiantly.

“Ever so much,” endorsed Meville.

“Let’s talk of other things,” said Chatteris. “It’s what the street boys call mawbid nowadays to doubt for a moment in the final all-this-and-nothing-else-in-the worldishness of whatever you happen to be doing.”

The interview had done my cousin good. His misery and distress had lifted. He was presently bathed in a profound moral indignation, and that is the very antithesis of doubt and unhappiness. The more he thought it over, the more his indignation with Chatteris grew. That sudden unresaonable outbreak altered all the perspectives of the case. He wished very much that he could meet Chatteris again and discuss the whole matter from a new footing.

“Think of it!” He thought so vividly and so verbally that he was nearly talking to himself as he went along. It shaped itself into an outspoken discourse in his mind.

“Was there ever a more ungracious, ungrateful, unreasonable creature than this same Chatteris? He was the spoiled child of Fortune; things came to him, things were given to him, his very blunders brought more to him than other men’s successes. Out of every thousand men, nine hundred and ninety-nine might well find food for envy in this way luck had served him. Many a one has toiled all his life and taken at last grateful the merest fraction of all that had thrust itself upon this insatiable thankless young man. Even I,” thought my cousin, “might envy him—in several ways. And then, at the mere first onset of duty, nay!—at the mere first whisper of restraint, this insubordination, this protest and flight!

“Think!” urged my cousin, “of the common lot of men. Think of the many who suffer from hunger—“

(It was a painful Socialistic sort of line to take, but in his mood of moral indignation my cousin pursued it relentlessly.)

“Think of the many who suffer from hunger, who lead lives of unremitting toil, who go fearful, who should go squalid, and withal strive, in a sort of dumb, resolute way, their utmost to do their duty, or at any rate what they think to be their duty. Think of the chaste poor women in the world! Think again of the many honest souls who aspire to the service of their kind, and are so hemmed about and preoccupied that they may not give it! And then this pitiful creature comes, with his mental gifts, his gifts of position and oppurtunity, the stimulus of great ideas, and a fiancee, who is not only rich and beautiful—she is beautiful!—but also the best of all possible helpers for him. And he turns away. It isn’t good enough. It takes no hold upon his imagination, if you please. It isn’t beautiful enough for him, and that’s the plain truth of the matter. What does the man want? What does he expect?…”

My cousin’s moral indignation took him the whole length of Piccadilly, and along by Rotten Row, and along the flowery garden walks almost into Kensington High Street, and so around by the Serpentine to his home, and it gave him such an appetite for dinner as he had not had for many days. Life was bright for him all that evening, and he sat down at last, at two o’clock in the morning before a needlessly lit, delightfully fusillading fire in his flat to smoke one sound cigar before he went to bed.

“No,” he said suddenly, “I am not mawbid either. I take the gifts the gods will give me. I try to make myself happy, and a few other people happy, too, to do a few little duties decently, and that is enough for me. I don’t look too deeply into things, and I don’t look too widely about things. A few simple ideals—

“Addy? Oh, she’s been going it. Comes downstairs and does the pale-faced heroine and goes upstairs and does the broken-hearted part. I know. It’s all very well. You never had sisters. You know—”

“There’s about a hundred blessed relatives of his in the place—came like crows for a corpse. I never saw such a lot. Talk about a man of good old family—it’s decaying! I never saw such a high old family in my life. Aunts they are chiefly.”

“Aunts?”

“Aunts. Say they’ve rallied round him. How they got hold of it I don’t know. Like vultures. Unless the mater—But they’re here. They’re all at him—using their influence with him, threatening to cut off legacies and all that. There’s one old girl at Bate’s Lady Poynting Mallow—least bit horsey, but about as right as any of ’em—who’s been down here twice. Seems a trifle disapointed in Adeline. And there’s two aunts at Wampach’s—you know the sort that stop at Wampach’s—regular hothouse flowers—a watering potful of real icy cold water would kill both of ’em. And there’s one who come over from the Continent, short hair, short skirts—regular terror—She’s at the Pavilion. They’re all chasing round saying, ‘Where is this women-fish sort of thing? Let me peek!'”

“They’re taking it in. Mainly they grasp the fact he’s going to jilt Adeline, just as he jilted the American girl. The mermaid side they seem to boggle at. Old people like that don’t take to a new idea all at once. The Wampach ones are shocked—but curious. They don’t believe for a moment she really is a mermaid, but they want to know all about it. And the one down at the Pavilion simply said, “Bosh!,” How can she breathe under water? Tell me that, Mrs. Bunting. She’s the sort of person you have picked up, I don’t know how but mermaid she cannot be.’ They’d be all trememndously down on the mater, I think, for picking her up, if it wasn’t that they can’t do without her help to bring Addy round again. Pretty mess all round, eh?”

Adjusting the folds of his blanket to a greater dignity.

“And every one,” she said, “blames me. Every one.”

“Everybody blames everybody who does anything, in affairs of this sort,” said Melville. “You musn’t mind that.”

“I’ll try not to,” she said bravely. “You know, Mr. Melville—“

“It was Addy. He went away and something in his manner made her write and ask him the reason why. So soon as she had his letter saying he wanted to rest from politics for a little, that somehow he didn’t seem to find the interest in life he thought it deserved, she divined everything—”

And as she talked, the problem before my cousin assumed graver and yet graver proportions. He percieved more and more clearly the complexity of the situation with which he was entrusted. In the first place it was not at all clear that Miss Glendower was willing to receive back her lover except upon terms, and the Sea Lady, he was quite sure, did not mean to release him from any grip she had upon him. They were preparing to treat an elemental struggle as if it were an individual case. It grew more and more evident to him how entirely Mrs. Bunting overlooked the essentially abnormal nature of the Sea Lady, how absolutely she regarded the business as a mere every-day vacilation, a common place outbreak of that jilting spirit which dwells, covered deep, perhaps, but never entirely eradicated in the heart of man; and how confidently she expected him, with a little tactful remonstrance and pressure, to prestore the status quo ante.

“She wants to speak to you,” said Mrs. Bunting, and Melville with a certain trepidation went upstairs. He went up to the big landing with the seats, to save Adeline the trouble of coming down. She appeared dressed in a black and violet tea gown with much lace and her dark hair was done with a simple carefulness that suited it. She was pale, and her eyes showed traces of tears, but she had a certain dignity that differed from her usual bearing in being quite unconscious.

“He is—he is a man with rather a strong imagination.”

“Or a weak will?”

“Relatively—yes.”

“It is so strange,” she sighed. It is so inconsistent. It is like a child catching at a new toy. Do you know, Mr. Melville”—she hesitated—“all this has made me feel old. I feel very much older, very much wiser than he is. I cannot help it. I am afraid it is for all women… to feel that sometimes.”

She reflected profoundly. “For all women—The child, man! I see now just what Sarah Grand meant by that.”

She smiled a wan smile. I feel as if he had been a naughty child. And I—I worshiped him, Mr. Melville,” she said, and her voice quivered.

My cousin coughed and turned about to stare hard out of the window. He was, he perceived, much more shockingly inadequate even than he had expected to be.

If I thought she could make him happy!” she said presently, leaving a hiatus of generous self-sacrifice.

“The case is—complicated,” said Melville.

Her voice went on, clear and a little high, resigned, inpenetrably assured.

“But she would not. All his better side, all his serious side—she would miss it and ruin it all.”

“Does he—” began Melville and repented the temerity of his question.

“Yes?” she said.

“Does he—ask to be released?”

“No… He wants to come back to me.”

“And you—“

“He doesn’t come.”

“But do you—do you want him back?”

“How can I say, Mr. Melville? He does not say certainly even that he wants to come back.”

My cousin Melville looked perplexed. He lived on the superfices of emotion and these complexities in matters he had always assumed were simple, put him out.

“There are times,” she said, “when it seems that my love for him is altogether dead… Think of the disillusionment—the shock—the discovery of such weakness.”

My cousin lifted his eyebrows and shook his head in agreement.

“His feet—to find his feet were of clay!”

There came a pause.

“It seems as if I have never loved him. And then—and then I think of all the things that still might be.”

Her voice made him look up, and he saw that her mouth was set hard and tears were running down her cheeks.

It occured to my cousin, he says, that he would touch her hand in a sympathetic manner, and then it occured to him that he wouldn’t. Her words rang in his thoughts for a space, and then he said somwhat tardily, “He may still be all those things.”

“I suppose he may,” she said slowly and without colour. The weeping moment had passed.”

“You are austere. You are restrained. Life—for a man like Chatteris is schooling. He has something—something perhaps more worth having than most of us have—but I think at times it makes life harder for him than it is for a lot of us. Life comes at him, with limitations and regulations. He knows his duty well enough. And you—you musn’t mind what I say too much, Miss Glendower—I may be wrong.”

“Go on,” she said, “go on.”

“You are too much—the agent general of his duty.”

You see you have defined things—very clearly. You have made it clear to him what you expect him to be, and what you expect him to do. It is like having built a house in which he is to live. For him, to go to her is like going out of a house, a very fine and dignified house, I admit, into something larger, something adventurous and incalculable. She is—she has an air of being—natural. She is as lax and lawless as the sunset, she is as free and familiar as the wind. She doesn’t—if I may put it in this way—she doesn’t love and respect him when he is this, and disapprove of him highly when he is that; she takes him altogether. She has the quality of the open sky, of the flight of birds, of deep tangled places, she has the quality of the high sea. That I think is what she is for him, she is the Great Outside. You—you have the quality—“

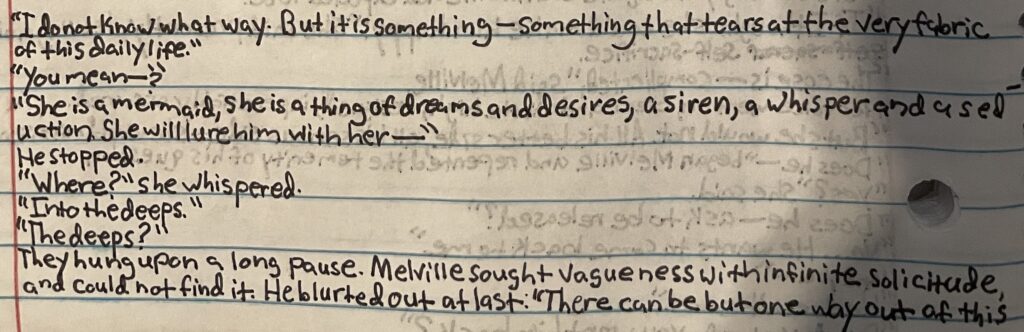

“I do not know what way. But it is something—something that tears at the very fabric of this daily life.”

“You mean—?”

“She is a mermaid, she is a thing of dreams and desires, a siren, a whisper and a seduction. She will lure him with her—“

He stopped.

“Where?” she whispered.

“Into the deeps.”

“The deeps?”

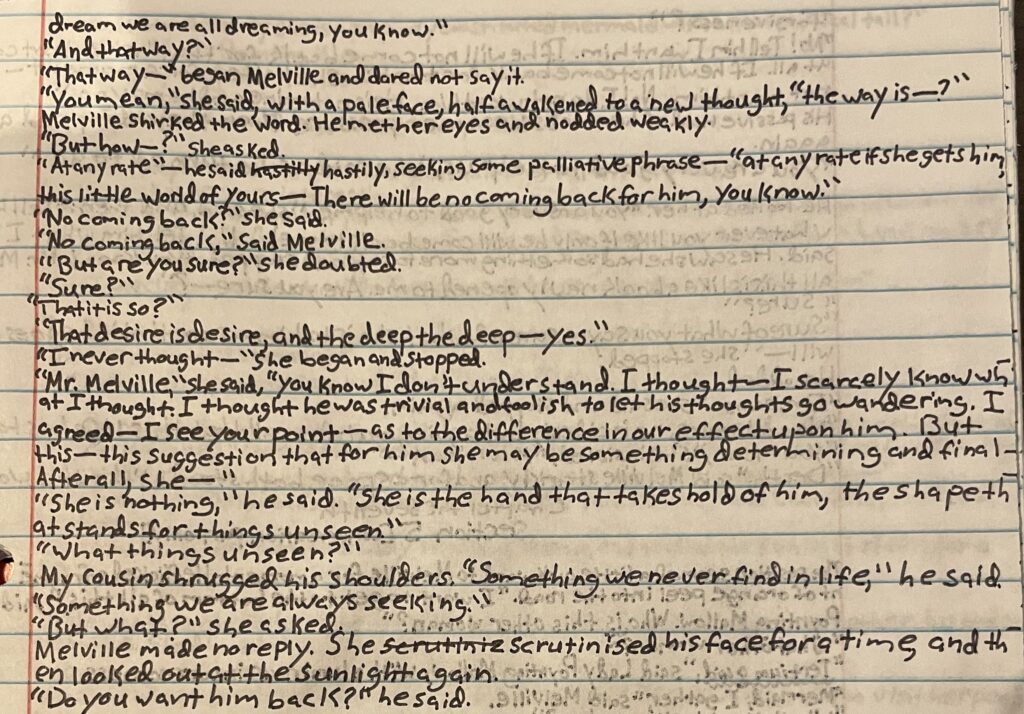

They hung upon a long pause. Melville sought vagueness with infinite solicitude and could not find it. He blurted out at last. “There can be but one way out of this dream we are all dreaming, you know.”

“And that way?”

“That way—began Melville and dared not say it.

You mean,” she said, with a plae face, half awakened to a new thought, “the way is—?”

Melville shirked the word. He met her eyes and nodded weakly.

“But how—?” she asked.

“At any rate”— he said hastily, seeking some palliative phrase— “at any rate if she gets him, this little world of yours—There will be no coming back for him, you know.”

“Now coming back?” she said.

“No coming back,” said Melville.

“But are you sure?” she doubted

“Sure?”

“That it is so?”

That desire is desire, and the deep the deep—yes.”

“I never thought—” she began and stopped.

“Mr. Melville,” she said, “you know I don’t understand. I thought—I scarcely know what I thought. I thought he was trivial and foolish to let his thoughts go wandering. I agreed—I see your point—as to the difference in our effect upon him. But this—this suggestion that for him she may be something determining and final—After all she—“

“She is nothing,” he said. “She is the hand that takes hold of him, the shape that stands for things unseen.”

“What things unseen?”

Melville made no reply. She scrutinised his face for a time, and then looked out at the sunlight agian.

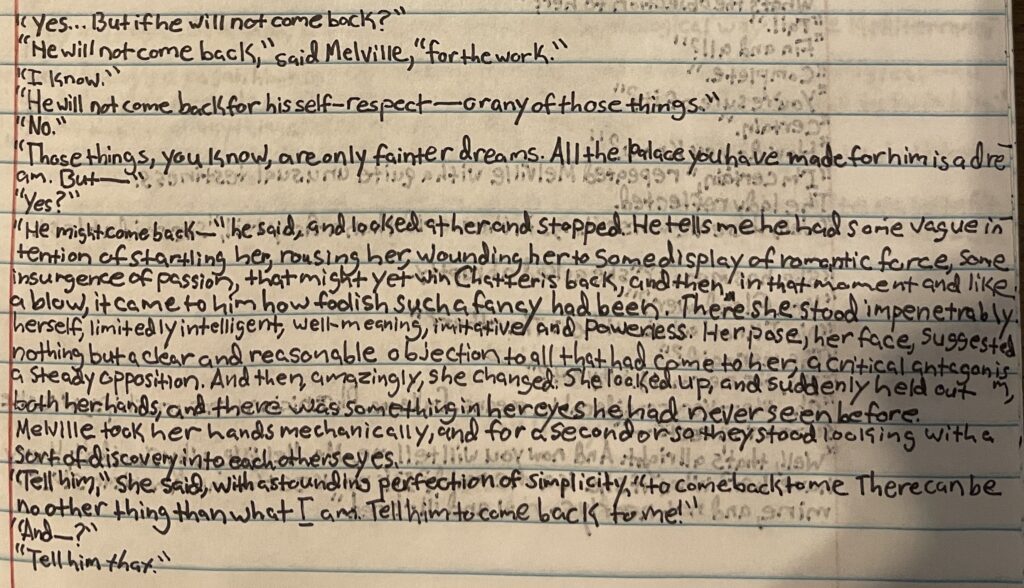

“Do you want him back?” he said.

“Yes… But if he will not come back?

He will not come back,” said Melville, “for the work.”

“I know.”

“He will not come back for his self-respect—or any of those things.”

“No.”

“Those things, you know, are only fainter dreams. All the palace you have made for him is a dream. But—“

“Yes?”

“He might come back—” he said, and looked at her and stopped. He tells me he had some vague intention of startling her, rousing her, wounding her to some display of romantic force, some insurgence of passion, that might yet win Chatteris back, and then in that moment and like a blow, it came to him how foolish such a fancy had been. There she stood impenetrably herself, limitedly intelligent, well-meaning, imitative and powerless. Her pose, her face, suggested nothing but a clear and reasonable objection to all that had come to her, a critical antagonism, a steady opposition. And then, amazingly, she changed. She looked up, and suddenly held out both her hands, and there was something in her eyes he had never seen before.

Melville took her hands mechanically, and for a second or so they stood looking with a sort of discovery into each others eyes.

“Tell him,” she said, with astouding perfection of simplicity, “to come back to me. There can be no other thing than what I am. Tell him to come back to me!”

“And—?”

“Tell him that.“

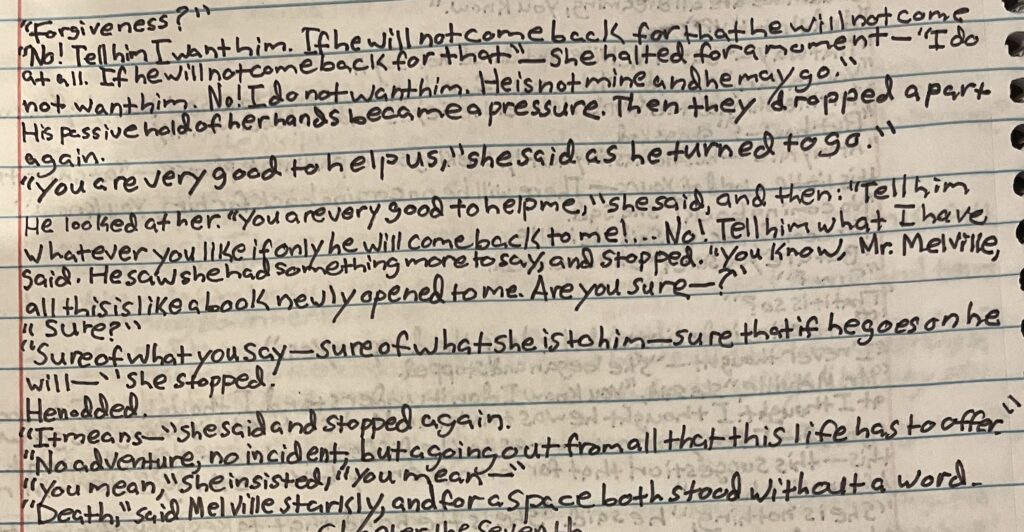

“Forgiveness?”

“No! Tell him I want him. If he will not come back for that he will not come at all. If he will not come back for that”—she halted for a moment—“I do not want him. No! I do not want him. He is not mine and he may go.”

His passive hold of her hands became a pressure. Then they dropped a part again.

“You are very good to help us,” she said as he turned to go.”

He looked at her. “You are very good to help me,” she said, and then: “Tell him whatever you like if only he will come back to me!…No! Tell him what I have said. He saw she had something more to say, and stopped. “You know, Mr. Mellville, all this is like a book newly opened to me. Are you sure—?”

“Sure?”

“Sure of what you say—sure of what she is to him—sure that if he goes on he will—” she stopped.

He nodded.

“It means—” she said and stopped again.

“No adventure, no incident, but a going out from all that this life has to offer.”

“You mean,” she insisted, “you mean—“

“Death,” said Melville starkly, and for a space both stood without a word.

The position seemed a little awkward to Melville for a moment. He flicked a fragment of orange peel into the road. “I want to get to the bottom of all this,” said Lady Poynting Mallow. Who is this other woman?

“What other woman?”

“Tertium quid,” said Lady Poynting Mallow, with a luminous incorretness.

“Mermaid, I gather,” said Melville.

“What’s the objection to her?”

“Tail.”

“Fin and all?”

“Complete.”

“You’re sure of it?”

“Certain.”

“How do you know?”

“I’m certain,” repeated Melville with a quite unusual testiness.

The lady reflected.

“Well, there are worse things in the world than a fishy tail,” she said at last.

“She has means?” she asked abruptly.

“Mrs Glendower?”

“No. I know all about her. The other?”

“The mermaid?”

“Yes, the mermaid. Why not?”

“Oh, she—very considerable means. Galleons. Phoenician treasure ships, wrecked frigates, submarine reefs—“

“Well, that’s all right. And now you will tell me, Mr. Melville, why shouldn’t Harry have her? What if she is a mermaid? It’s no worse than an American silver mine, and not nearly so raw and ill-bred.”

“You understand clearly she is a properly constituted mermaid with a real physical tail?”

“Well?” said Lady Poynting Mallow.

“Apart from any question of Miss Glendower—“

“That’s understood.”

“I think that such a marriage would be impossible.”

“Why?”

My cousin played round the question. “She’s an immortal with a past.”

“Simply makes her more interesting.”

Melville tried to enter into her point of view. “You think,” he said, “She would go to London for him, and marry at St. George’s, Hanover Square, and pay for a mansion in Park Lane and visit just anywhere he liked?”

“That’s precisely what she would do. Just now, with a Court that is waking up—“

“She doesn’t even mean to marry him; it doesn’t enter into her code.”

“The hussy! What does she mean?”

My cousin made a gesture seaward. “That!” he said. “She’s a mermaid.”

Lady Poynting Mallow scanned the sea as if it were some curious new object. “It’s an amphibious outlook for the family,” she said after reflection. “But even then—if she doesn’t care for society and it makes Harry happy—and perhaps after they are tired of—rusticating—“

I don’t think you fully realise that she is a mermaid,” said Melville; “and Chatteris, you know, breathes air.”

“That is a difficulty,” admitted Lady Poynting Mallow, and studied the sunlight offing for a space.

“If she wants him badly he might make terms. In these affairs it’s always one or other has to do the buying. She’d have to marry anyhow.”

My cousin regarded her inpenetrably satisfied face.

“He could have a yacht and a diving bell,” she suggested, “if she wanted him to visit her people.”

“They are pagan demigods, I believe, and live in some mythological way in the Mediterranean.”

“Dear Harry’s a pagan himself—so that doesn’t matter, and as for being mythological—all good families are. He could even wear a diving dress if one could be found to suit him.”

“I don’t think that anything of the sort is possible for a moment.”

“Simply because you’ve never been a woman in love,” said Lady Poynting Mallow with an air of vast experience.

She continued the conversation. “If it’s sea water she wants it would be quite easy to fit up a tank wherever they lived, and she could easily have a bath chair like a sitz bath on wheels… Really, Mr. Milvain—”

“Melville.”

“Dear no!” It’s Harry’s place to settle that. But I’ve seen her in her bath chair on the Leas, and I’m certain I’ve never seen anyone who looked so worthy of dear Harry. Never!”

“Well, well,” said Melville, “Apart from any other considerations, you know, there’s Miss Glendower.”

“Possibly not. Still—she exists.”

“So many people do,” said Lady Poynting Mallow.

She evidently regarded that branch of the subject as dismissed.

“She ought to be devoted to him—yes. Well, why can’t she see that she ought to release him for his own good?”

“She doesn’t see it’s for his good. Nor do I.”

“Simply an old-fashioned prejudice because the woman’s got a tail. Those old frumps of wampach’s are quite of your opinion.”

“May I ask what you are going to do?”

“What a good aunt always does.”

“And that?”

“Let him do what he likes.”

“Suppose he wants to drown himself?”

“My dear Mr. Milvain, Harry isn’t a fool.”

“I’ve told you she’s a mermaid.”

“Ten times.”

A constrained silence fell between them.

It became apparent they were near the Folkestone Lift.

“You’ll do no good,” said Lady Poynting Mallow.

In the course of another minute Melville found himself on the side of the road opposite the lift station, regarding the ascending car. The boldly trimmed bonnet, vivid, erect, assertive, went gliding upward, a perfect embodiment of sound common sense. His mind was lapsing once again into disorder, he was stunned, as it were, by the vigour of her ladyship’s view. Could any one not absolutely right be quite so clear and emphatic? And if so, what became of all that oppression of foreboding, that sinister promise of an escape, that whisper of “other dreams,” that had dominated his mind only a short half-hour before?

He turned his face back to Sandgate, his mind a theatre of warring doubts. Quite vividly he could see the Sea Lady as Lady Poynting Mallow saw her, as something pink and solid and smart and wealthy, and, indeed, quite abominably vulgar, and yet quite as vividly he recalled her as she had talked to him in the garden, her face full of shadows, her eyes of deep mystery, and the whisper that made all the world about him no more than a flimsy, thin curtain before vague and wonderful, and hitherto, quite unsuspected things.

“I know,” said Chatteris and flicked again at that ghostly ash, “She has written that… That’s just where her complete magnificence comes in. She doesn’t fence and fool about, as the she-women do. She doesn’t squawk and say, ‘You’ve insulted me and everything’s at an end;’ and she doesn’t squawk and say, ‘For God’s sake come back to me!’ She doesn’t say, she ‘won’t ‘ave no truck with me not after this.’ She writes—straight. I don’t believe, Mellville, I half knew her until all this business came up. She comes out…. Before that it was, as you said, and I quite perceive—I perceived all along—a little too statistical.”

“She’s not beautiful to every one.”

“You mean?”

“Bunting keeps calm.”

“Oh—he—!”

“And other people don’t seem to see it—as I do.”

“Some people seem to see no beauty at all, as we do. With emotion, that is.”

“Why do we?”

“We see—finer.”

“Do we? Is it finer? Why should it be finer to see beauty where it is fatal to us to see it? Why? Unless we are to believe there is no reason in things, why should this—impossibility, be beautiful to any one anyhow? Put it as a matter of reason, Mellville. Why should her voice move me! Why her’s and not Adeline’s? Adeline has straight eyes and clear eyes and fine eyes, and all the difference there can be, what is it? An infintesimal curving of the lid, an infintesimal difference in the lashes—and it shatters everything—in this way. Who could measure the difference, who could tell the quality that makes me swim in the sound of her voice… The difference? After all, it’s a visible thing, it’s a material thing! It’s in my eyes. By Jove!” he laughed abruptly. “Imagine old Helmholtz trying to gauge it with a battery of resonators, or Spencer in the light of Evolution and the Enviornment explaining it away!”

“These things are beyond measurement,” said Melville.

“Not if you measure them by their effect,” said Chatteris. “And anyhow, why do they take us? That is the question I can’t get away from just now.”

My cousin meditated, no doubt with his hands deep in his trousers’ pockets. “It is illusion,” he said. “It is a sort of glamour. After all, look at it squarely. What is she? What can she give you? She promises you vague somethings… She is a snare, she is deception. She is the beautiful mask of death.”

“There is nothing for me to learn about that,” he said. “But why—why should the mask of death be beautiful? After all—We get our duty by good hard reasoning. Why should reason and justice carry everything? Perhaps after all there are things beyond our reason, perhaps after all desire has a claim on us?”

He stopped interrogatively and Melville was profound. “I think,” said my cousin at last, “Desire has a claim on us. Beauty at any rate—”

“I mean,” he explained, “we are human beings. We are matter with minds growing out of ourselves. We reach downward into the beautiful wonderland of matter, and upward to something—” He stopped, from sheer dissatisfaction with the image. “In another direction, anyhow,” he tried feebly. He jumped at something that was not quite his meaning. “Man is a sort of half-way house—he must compromise.”

“As you do?”

“Well. Yes. I try to strike a balance.”

“A few old engravings—good, I suppose— a little luxury in furniture and flowers, a few things that come within your means. Art—in moderation, and a few kindly acts of the pleasanter sort, a certain respect for truth; duty—also in moderation. Eh? It’s just that even balance that I cannot contrive. I cannot sit down to the oatmeal of this daily life and wash it down with a temperate draught of beauty and water. Art!…I suppose I’m voracious, I’m one of the unfit—for the civilised stage. I’ve sat down once, I’ve sat down twice, to perfectly sane, secure, and reasonable things… It’s not my way.”

“But, after all, what is the good of talking in this way?” exclaimed Chatteris abruptly. “I am simply trying to elevate the whole business by dragging in these wider questions. It’s justification when I didn’t mean to justify. I have to choose between life with Adeline and this woman out of the sea.”

“Who is Death.”

“How do I know she is Death?”

“But you said you had made your choice!”

“I have.”

Melville produced an elaborate conceit. “If there is no Venus Anadyomene,” he said, “there is Michael and his Sword.”

“The stern angel in armour! But then he had a good palpable dragon to slash and not his own desires. And our way nowadays is to deal with dragons somehow, raise the minimum wage and get better housing for the working classes by hook or by crook.”

“No,” said Chatteris, “I’ve no doubt about the choice. I’m going to fall in—with the species; I’m going to take my place in the ranks in that great battle for the future which is the meaning of life. I want a moral cold bath and I mean to take one. This lax dalliance with dreams and desires must end. I will make a time table for my hours and a rule for my life, I will entangle my honour in controversies, I will give myself to service, as a man should do. Clean-handed work, struggle and performance.”

“And there is Miss Glendower, you know.”

“Rather!” said Chatteris, with a faint touch of insincerity. “Tall and straight-eyed and capable. By Jove! if there’s to be no Venus Anadyomene, at any rate there will be a Pallas Athene. It is she who plays the reconciler.”

“I want a good, gray, honest day,” he said, “with a south-west wind… These still, soft nights! How can you expect me to do anything of that sort to-night?”

The valet’s evidence is precise, but has an air of being irrelevant. He witnesses that at a quarter past eleven he went up to ask Chatteris if there was anything more to do that night, and found him seated in an arm-chair before the open window, with his chin upon his hands, staring at nothing—which indeed, as Schopenhauer observes in his crowning passage, is the whole of human life.

Probably Chatteris remained in this attitude for a considerable time—half an hour, perhaps, or more. Slowly, it would seem his mood underwent a change. At some moment it must have been that his lethargic meditation gave way to a strange activity, to a sort of hysterical reaction against all his resolves and renunciations. His first action seems to me grotesque and grotesquely pathetic. He went into his dressing-room, and in the morning “his clo’es,” said the valet, “was shied about as though ‘ed lost a ticket.” This poor worshipper of beauty and the dream shaved! He shaved and washed and he brushed his hair, and, his valet testifies, one of the brushes got “shied” behind the bed. Even this throwing about of brushes seems to me to have done little or nothing to palliate his poor human preoccupation with the toilette. He changed his gray flannels—which suited him very well—for his white ones, which suited him extremely. He must deliberately and conscientiously have made himself quite “lovely,” as a schoolgirl would have put it.

I gather that the Sea Lady put on a loose wrap, and the faithful Parker either carried her or sufficiently helped her from her bedroom to the couch in the little sitting-room. In the meanwhile the hall-porter hovered on the stairs, praying for the manager—prayers that went unanswered—and Chatteris fumed below. Then we have a glimpse of the Sea Lady.

“I see her just in the crack of the door,” said the porter, “as that maid of hers opened it. She was was raised upon her hands, and turned so towards the door. Looking exactly like this—“

And the hall-porter, who has an Irish type of face, a short nose, long upper llip, and all the rest of it, and who has also neglected his dentist projected his face suddenly, opened his eyes very wide, and slowly curved his mouth into a fixed smile, and so remained until he judged the effect on me was complete.

Parker, a little flushed, but resolutely flattening everything to the quality of the commonplace, emerged upon him suddenly. Miss Waters could see Mr. Chatteris for a few minutes. She was emphatic with the “Miss Waters,” the more emphatic for all the insurgent stress of the goddess, protestingly emphatic. And Chatteris went up, white and resolved, to that smiling expectant presence. No one witnessed their meeting but Parker—assuredly Parker could not resist seeing that, but Parker is silent—Parker preserves a silence rubies could not break. All I know, is this much from the porter:

“I couldn’t find the manager to tell ‘im,” said the hall-porter. “And what was I authorized to do?

“For a bit they talked with the door open, and then it was shut. That maid of hers did it—I lay.”

I asked an ignoble question.

“Couldn’t ketch a word,” said the hall-porter. “Dropped to whispers—instanter.”

Section 2 of Chapter the Eighth

And afterwards—

It was within ten minutes of one that Parker, conferring an amount of decorum on the request beyond the power of any other living being, descended to demand—of all conceivable things—the bath chair!

And then, having let me realise the fulness of that, he said: “They never used it!”

“No?”

“No! He carried her down in his arms.”

“And out?”

“And out!”

He was difficult to follow in his description of the Sea Lady. She wore her wrap it seems, and she was “like a statue.” Whatever he may have meant by that. Certainly not that she was impassive. “Only,” said the porter, “she was alive. One arm was bare, I know, and her hair was down, a tossing mass of gold.

“He looked, you know, like a man who’s screwed himself up.

“She had one hand holding his hair—yes, holding his hair, with her fingers in among it….

“And when she see my face she threw her head back laughing at me.

“As much as to say ‘got’ ‘im!”

“Laughed at me she did. Bubblin’ over.”

I stood for a moment conceiving this extraordinary picture. Then a question occured to me.

“Did he laugh?” I asked.

“Gord bless bless you, sir, laugh? No!”

They went through the soft moonlight, tall and white and splendid, interlocked, with his arms around her, his brow to her white shoulder and her hair about his face. And she, I suppose, smiled above him and caressed him and whispered to him. For a moment they must have glowed under the warm light of the lamp that is half-way down the steps there, and then the shadows closed about them. He must have crossed the road with her, through the laced moonlight of the tree shadows, and through the shrubs and bushes of the undercliff, into the shadeless moonglare of the beach. There was no one to see that last descent, to tell whether for a moment he looked back before he waded into the phosphorescence, and for a little swam with her, and presently swam no longer and so was to be seen no more by any one in this gray world of men.

Did he look back, I wonder? They swam together for a little while, the man and the sea goddess who had come for him, with the sky above them and the water about them all, warmly filled with the moonlight and set with the shining stars. It was no time for him to think of truth, nor of the honest duties he had left behind him, as they swam together into the unknown. And of the end I can only guess and dream. Did there come a sudden horror upon him at last, a sudden perception of infinite error, and was he drawn down, swiftly and terribly, a bubbling repentance, into those unknown deeps? Or was she tender and wonderful to the last, and did she wrap her arms about him and draw him down, down until the soft water closed above him into a gentle ecstasy of death?

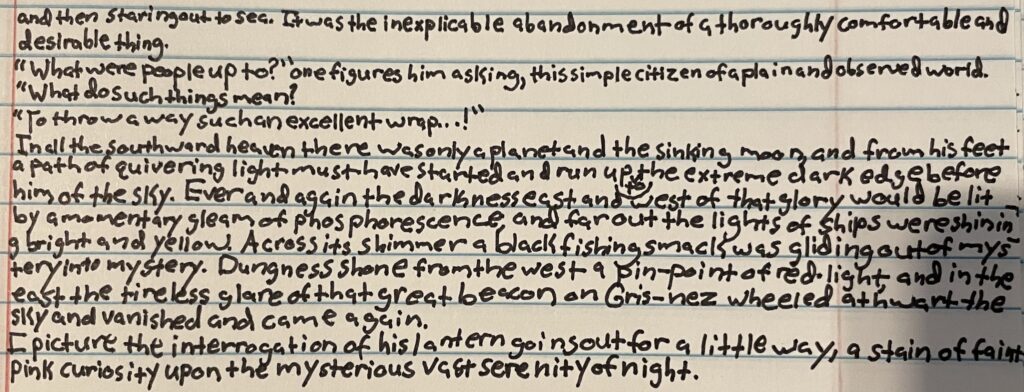

Into these things we cannot pry or follow, and on the margin of the softly breathing water the story of Chatteris must end. For the tailpiece to that, let us put that policeman who into the small hours before dawn came upon the wrap the Sea Lady had been wearing just as the tide overtook it. It was not the sort of garmet low people sometimes throw away—it was a soft and costly wrap. I seem to see him perplexed and dubious, wrap in charge over his arm, and lantern in hand, scanning first the white beach and black bushes behind him and then staring out to sea. It was the inexplicable abandonment of a throughly comfortable and desirable thing.

“What were people up to?” one figures him asking, this simple citizen of a plain and observed world. “What do such things mean?

“To throw away such an excellent wrap…!”

In all the southward heaven there was only a planet and the sinking moon, and from his feet a path of quivering light must have started and run up the extreme dark edge before him of the sky. Ever and again the darkness east and west of that glory would be lit by a momentary gleam of phosphorescence, and far out the lights of ships were shining bright and yellow. Across its shimmer a black fishing smack was gliding out of mystery into mystery. Dungness shone from the west a pin-point of red light and in the east the tireless glare of that great beacon on Gris-nez wheeled athwart the sky and vanished and came again.

I picture the interrogation of his lantern going out for a little way, a stain of faint pink curiosity upon the mysterious vast serenity of night.